Illustration by Cody Angell

|

By Caitlin Hall

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Friday November 8, 2002

"The death penalty is dead wrong," proclaims one of the buttons that I proudly display on my admittedly slogan-laden backpack. I wear it brazenly, eagerly anticipating a challenge, relentlessly begging my favorite question: why?

So · why? Why do I want to provoke people? What makes me so bold? In short, that which drives any devout proselytizer: research, conviction and the will to convert.

Justice Thurgood Marshall once wrote that there was no question as to whether the majority of Americans supported the death penalty; the question was as to whether they still would if confronted with adequate information. That question is as appropriate today as the day it was first posed. And sadly, the abolitionist cause suffers as acutely now from public misinformation as it did then.

The justifications for abolishing capital punishment are numerous. Before discussing them, however, let's be clear about who we're discussing. Advocates of the death penalty often appeal to the public by presenting mass murderers, serial killers and terrorists as the type of criminals the death penalty is designed to deal with. Don't believe it? When was the last time you read a pro-death penalty position that didn't make reference to Timothy McVeigh, John Muhammad, Charles Manson or another criminal of the same caliber?

While it is certainly true that capital punishment was instituted with people like these in mind, it is equally true that they are completely unrepresentative of the death row population. The average person sentenced to death has killed on one occasion and is distinguishable from someone receiving life in prison for a similar crime only in that he was too poor to afford adequate legal representation. (A side note: I use "he" throughout this column. Linguistically, I hate it. Statistically, it's correct.)

With that in mind, let's explore some of the arguments in favor of abolishing the death penalty. First: the obligatory cost analysis. Personally, I don't believe cost should be a factor in weighing matters of justice. However, one of the most popular stances of death penalty advocates is that the money used to keep a murderer in prison could be better used elsewhere. Therefore, it bears stating: Executing someone costs more than imprisoning him for life. In fact, when the legal costs of the lengthy appeals process for a capital case are factored in, it is on average three times more expensive to execute a criminal than to keep him in a maximum-security prison for the rest of his life without the possibility of parole.

Moreover, the claim that someone serving a sentence of life without the possibility of parole ÷ the alternative to capital punishment ÷ poses more of a continued threat to society than someone facing the death penalty is unfounded. The average inmate spends a decade on death row before execution. Logically speaking, who, if anyone, poses more of a threat of escape: the person who knows he will spend the rest of his natural life in prison or the person who knows with near-absolute certainty when and where he will die if he does nothing to circumvent it?

Let's assume for the time being that we have a justice system immune to error ÷ that is, one in which everyone convicted of a capital offense is actually guilty of one. Even if that were true, how consistent or conscionable is the way the death penalty is applied?

A modern code of ethics dictates that in order to sentence someone to death for a crime, we must believe he was aware of his actions and their consequences. It is conventionally assumed within the scope of U.S. law that a person under the age of 18 lacks the mental and moral abilities to make responsible decisions ÷ or, to put it another way, decisions for which he may reasonably be held responsible. Given these principles, it is baffling that we continue to execute people who were juveniles at the time of their crime.

We do so in violation of every international treaty that addresses the intersection of human rights and capital punishment. The United States is one of only seven countries in the world to have executed people convicted as juveniles in the last decade, and we continue to do so more often than any of the other countries ÷ Iran, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, which has since outlawed the practice. If that isn't enough to stir your conscience, consider that children as young as 14 have been executed in the last century in the United States.

Furthermore, we are one of only three countries that continues to execute the mentally ill. As if that weren't reprehensible enough, the death penalty is imposed arbitrarily, and often discriminatorily, in such cases. James Colburn, a Texas man with severe paranoid schizophrenia, is currently at the last stage of appeal in his death penalty trial. Despite claiming not to be in control of his actions during his crime (the murder of an adult female), sleeping through his trial because of anti-psychotic tranquilization and spending most of his time on death row in a psychiatric ward because he ate his own feces and tried to kill himself every time he was discharged, Colburn was found competent both to stand trial and be executed.

Now consider the case of Andrea Yates, also of Texas. She was found guilty of brutally murdering her five children, but was spared the death penalty because of a combination of severe depression and public outcry at the prospect of her execution. It seems difficult to reconcile the crimes and circumstances of these two cases while maintaining belief in the consistency and fairness of the death penalty's application.

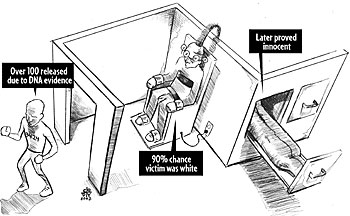

On a larger scale, a more egregious injustice is evident in death penalty statistics. Although people of color constitute more than half of all homicide victims in the United States, 90 percent of all death row victims are white. Death penalty proponents will be quick to point out that there is not a strong correlation between the race of the convicted and the frequency with which death sentences are handed down. However, as long as there is a correlation between that incidence and the race of the victim, the message is exactly the same: The life of a white person is worth more than that of a person of color.

I asked you earlier to pretend that our justice system was one immune to error. If that didn't require a major suspension of belief, you haven't been paying enough attention. Our system does not separate the innocent from the guilty. It has failed in situations in which failure should never be an option. The finality and enormity of such a punishment demand absolute confidence in the righteousness of the justice system, and that is a certainty no educated person can offer. Over one hundred innocent inmates have been released from death row on the basis of DNA evidence. Twenty-three ÷ that we know of ÷ weren't so fortunate. Who could have confidence in a system that allows an innocent person to bear the ultimate punishment, a brutal and untimely death? It is not tragic; it is criminal. We cannot continue to execute people while we look for solutions to the system's problems. To err is human. To create a system that makes that error irreparable is inhumane.

Finally, the concept of the death penalty as a deterrent deserves some attention. To begin with, it is worth stating what a deterrent is: an example, a penalty levied not in punishment of a crime committed, but as a preventive measure against future crime. I don't mean to say that this is the only merit death penalty advocates find in capital punishment, but it's an interesting concept nonetheless.

That said, does the death penalty deter crime? There is no evidence to suggest that it does. In fact, states that allow the death penalty have average murder rates twice that of those that don't allow it, and states and nations which have abolished the death penalty have generally witnessed reductions in the incidence of violent crime, rather than increases.

What could account for this counterintuitive trend? It is symptomatic of the paradox of the death penalty: a system seeks to punish crime via its propagation. We cannot condemn killing by killing; we can only condone it. Such is the problem inherent in legislating vengeance. The death penalty institutionalizes and legitimates a cycle of brutality, presenting violence as an appropriate way of dealing with society's shortcomings.

The death penalty as it is applied in the United States is racially biased, costly and arbitrary; it is responsible for the deaths of juveniles, the mentally ill and the innocent; and it legitimizes murder. Given this, what is the answer to Marshall's question?

Will we continue to support the death penalty, even when reason provides no justification? Or will we finally join the overwhelming majority of nations in the world in abandoning it?