|

|

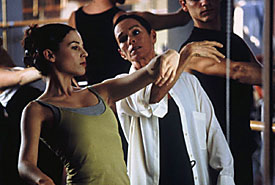

PHOTO COURTESY OF SONY PICTURES

|

"Talk To Her" is another film from acclaimed Spanish director Pedro Almodovar. He is nominated for an Academy Award in directing this year.

|

|

By Mark Betancourt & Lindsay Utz

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Thursday February 13, 2003

Betancourt: Unfortunately for us, "Talk To Her" is the sort of film that shouldn't be talked about, but watched. Not that you'll necessarily like it, but nothing we say can really describe what it's like.

Utz: "Talk to Her" is breathtaking, heartbreaking, eloquent and beautiful. These are the words that come to mind, but really, like you said, there are no words to describe this truly indescribable film. Spanish director Pedro Almodovar ("All About My Mother") once again proves that originality still exists and that it's possible to create rich stories that mean something. But unlike his two previous films, this one is not as bizarre or hectic. Instead, "Talk to Her" is calm, steadily paced and more focused.

Betancourt: The part where the miniature silent film character climbs into his lover's vagina and stays there forever ÷ where exactly does that fit into "not as bizarre"?

Utz: Okay, yes, that was so bizarre · and so beautiful. If only men would just stop talking, shrink, giggle and jump into women's vaginas more often, this would be a more peaceful world. If George and Saddam and all the other bastard men would just shrink and crawl into their wives' vaginas, maybe we wouldn't be on the brink of war, or have war at all. And I'm serious here, I think Almodovar is saying something important with all his films about women and emotional men and people who, although they do things that are bad, are human ÷ a fundamental truth we all too often forget.

Betancourt: Well, let's at least say something about the actual story before we get into all that. Like all of Almodovar's films, "Talk To Her" follows a handful of characters whose connections to each other, while apparently circumstantial at first, become clearer and deeper as the story goes on. Benigno (Javier Camara) is a simple-minded nurse whose daily charge is to care for Alicia (Leonor Watling), a young woman in a coma. Marco (Dario Grandinetti) is a journalist in love with the famous bullfighter Lydia (Rosario Flores). The story begins in earnest when Lydia is gored in the bullfighting ring and slips into a coma identical to Alicia's. The rest of the film is devoted to drawing Marco and Benigno together in a devoted friendship and a mutual appreciation for the mysteries of women, life and love.

Utz: What struck me the most is how, with the beautiful Spanish score, the film becomes one long, lovely waltz. In fact, the film both opens and closes with dancers, entranced in their movements. To dance is to surrender your body and mind to the uninterrupted flow of something streaming, something ethereal and greater than yourself that, for a moment, takes over. It's beauty. We have Marco, whose response to this beauty, in the form of pain or joy, is to cry. And then there's Benigno whose response is, well, I won't give it away. Let's just say it isn't what you'd expect. Almodovar, with the help of some extraordinary actors and super camera work, creates a world where loneliness and sadness are beautiful. There is a very divine sense to the film, like an out-of-body experience, as if we, the audience, are dancers too.

Betancourt: At the risk of killing the mood, I think Almodovar might hover a little to close to overdoing his usual themes with this latest installment. His films are always about men and women, especially women and their relationships, personally and symbolically, with the world. These themes are almost always passionate and thoughtful ÷ drawing on symbols of femininity as old as Greek tragedy and the most modern of personal relationships ÷ to paint a moving portrait of woman as the center of a universe that refuses to die, despite its constant and irrepressible imperfection. Really, this stuff is that good. It's not even super artsy or hard to understand. These things just come through in the way the set is decorated or a little, perfect turn of phrase from the lips of the most naive characters. But every once in a while, the ideas get questionable. One has to ask why the women in this film spend most of it unconscious, which is in fact crucial to the way Almodovar wants to talk about them, rather than to them. Benigno tells Marco that women need to be listened to, made to feel special, cared for, and in essence, cultivated like plants. While his concept of femininity is complex, wrapped up to some degree in the idea that femininity is more of an essential compassion that emerges from the trivial pursuits of masculinity than a distinction between genders, it sometimes verges on over-simplicity. Almodovar's women are mysterious undiscovered countries who represent the better angels of our nature, but as characters, they really just sit there. What do you think, Utz?

Utz: His women didn't just sit in other films, quite the opposite actually because they were always running wild, nervous, sad ÷ with the exception of the spiked woman who passes out in "Women." So the fact that they're so motionless for most of this movie is a striking contrast. In "Talk to Her," two women lay still, as if entombed by bed sheets, lotioned and massaged by men who talk about them, adore them, look at them, remember them. It's the men here that are wild, desperate and lonely. Almodovar isn't making a gender distinction; he's actually drawing profound parallels. He is not making them out to be goddesses. Instead, he places them before us, before Benigno and Marco, and for some reason, when these women are in a position of peace and quiet and also vulnerability, these two men are able to face and deal with their own weaknesses and vulnerabilities. Almodovar is not elevating women, just quieting them for a moment and reminding us that men have emotions too.

Betancourt: Wow, Utz. Nicely done.