|

|

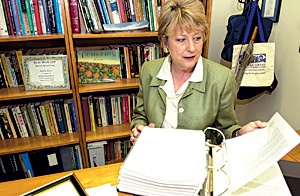

FILE PHOTO/Arizona Summer Wildcat

|

Barbara Becker, director of the School of Planning, reviews some of the letters written to the UA in the last several months in support of the school. The school's future has been threatened for more than a year.

|

|

|

By Mitra Taj

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Wednesday, July 21, 2004

Print this

Planning students and faculty fighting for the past 18 months to keep the graduate planning degree at the UA finally got the support they'd been waiting for from university administration.

UA President Peter Likins announced last week that instead of eliminating the School of Planning altogether, university administrators would rather see what's left of it reorganized into a planning program in the department of geography and regional development of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Likins will present the plan for approval by the Arizona Board of Regents next month.

The compromise, originally proposed by the faculty senate in April, will save the university money while continuing to grant students master's degrees in planning, a degree many said is necessary to help Southern Arizona tackle environmental and housing problems as the state's population explodes.

"We really look forward to rebuilding and being stronger than ever," said Barbara Becker, director of the planning school. "Once we get the word out, we'll be setting up more projects with students."

In anticipation of a possible closure, the planning school wasn't allowed to take in new students last fall and spring.

Since the school was first selected for elimination in January of 2003, Becker said the number of graduate students has shrunk from 68 to 20. It has also lost two faculty members.

Becker said she would like to see the program attract new students and hire on new faculty members.

But Provost George Davis said that while the university supports the planning program in its new home, it wouldn't be able to fund the additional expenses a bigger program could bring.

"As provost I'm not interested in investing new faculty members in the program," Davis said. "We want it to be a quality program. We don't anticipate it should expand significantly."

Becker said the program would look for its own funding by offering courses to planning professionals and fund-raising.

"We're not going to be asking (the university) for funding," Becker said. "But if we grow, we're going to find ways to support that growth."

If regents approve the plan in August, the department of geography and regional development will begin planning the best way to fit the new program, John Paul Jones, head of the department of geography and regional development, said. The new plan for planning will be ready in December.

"A lot of things need to be worked out," Jones said. "But this is the best way for the university to preserve planning."

Becker said the move out of the College of Architecture will allow the planning school to make social science issues a greater focus than design. She said she expects to work more with other departments in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences and the American Indian Studies program.

More planning undergrad courses are also likely, Becker said. "Hopefully we'll be getting more people interested in planning."

Jones said the possible planning school would be a "natural fit" in the department.

Jones said there are probably regional development majors interested in getting their master's in planning, but he said it remains to be seen whether or not many of the 250 majors will go on to the planning program.

Jones said he doesn't expect the new addition to stress the department's expense budget, and said together the two areas will stretch the university's budget more than if they continued operating independently.

Popular support saved school from being cut

Faculty, students and supporters of the School of Planning have vocally opposed possible elimination since Focused Excellence, a plan to emphasize the research mission of the university in the face of state budget cuts, proposed getting rid of it and 15 other academic programs.

While the School of Planning was one of seven programs spared elimination in April of 2003, months later university administration decided that moving it to the College of Public Health would still cost too much.

Becker said the support that poured in from all over the country has been essential in convincing the university of the school's importance.

Davis said the public outcry voiced against the elimination proposals made "so clear" how much the UA's academic programs served the public.

The planning school was one of the programs that inspired the most feedback, Davis said.

"Vital public impact" was listed as one of the criteria in considering which programs would be eliminated. The others were "educational excellence," "research and creative excellence," "student demand," "revenue generation" and "interdisciplinary need."

Public support for all of the programs is taken seriously, Davis said. "We read every letter; we have notebooks full of letters in support of the programs."

Becker said she has a large three-ring binder full of letters of support for the school from all over the country.

Among the organizations that spoke out to keep the school from disappearing were the Planning Accreditations Board, the American Planning Association and the American Institution of Architects, Becker said.

The planning school drew nationwide attention because of the unique concentrations - like environmental and healthy cities planning - it offers students.

"While other schools may teach one course, we were building healthier communities here in Arizona," Becker said.

Students who work on planning at the U.S.-Mexican border and on American Indian reservations are getting experience in a profession that might be "the wave of the future," Becker said.

School vital to growth of Tucson community

Daniel Tylutki, a native Tucsonan and planning graduate student interning at the housing department of the city of South Tucson, said getting rid of the degree would have done many communities in southern Arizona with few funds pay professional planners a "great injustice."

"Everyone that comes out of the school either works in Arizona or gets their start in Arizona," he said.

Andrew Gunning, regional planning director of the Pima Association of Governors, which takes in many planning students for internships and employment after graduation, said because planning laws vary from state to state, "local, home-grown talent," is essential to helping the region grapple with planning problems.

Gunning said planning interns have worked on a wide variety of projects, from transportation studies to congestion management plans.

"People that have done internships here and later work locally are more familiar with local conditions and problems," Gunning said.

Jennifer Dederich, a planning graduate student who works on environmental and economic development issues in the city of South Tucson, said managing to move the planning school to geography at a time when financial problems across the country are forcing universities to make tough decisions is great news.

"At least it's not dead," she said. "At least later it can grow if it's able to."

Tylutki agreed. "Planning is planning, no matter where it is," he said.

Tylutki said he loves the hands-on experience that is characteristic of the school.

"I help poor people get their houses fixed, in plain English," Tylutki said. "It's fun."

Tylutki and Dederich credit Becker's "sheer determination" with saving the graduate planning degree.

"She rallied the troops, she got the word out and made believers out of everybody," Tylutki said.

While Tylutki said the optimism of Becker made it hard for students and faculty to lose hope, he said "there were times when we just didn't know."

"We're happy to have Becker," Dederich said. "We're happy she stuck around and fought it out."