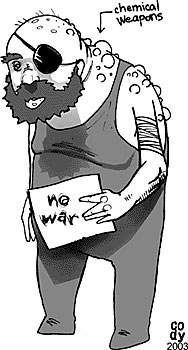

Illustration by Cody Angell

|

By Phil Leckman

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Monday April 7, 2003

If surprise was their goal, the protesters could hardly have picked a better venue than the Student Union Memorial Center food court. After all, few people associate McDonald's or Domino's with anti-war agitprop. This time, however, that's exactly what they got. As peace activists doused themselves with fake blood and dropped to the floor in simulation of Iraqi dead, the hungry lunchtime crowd found themselves confronted with a stark display of the strong emotions stirred up by the war in the gulf.

The words and feelings kicked up by last week's die-in are summarized elsewhere, so most of the angry rebuttals, heartfelt support, and exasperated apathy the demonstration produced will not be revisited here. One comment, however, deserves additional attention. When Arizona Daily Wildcat reporter Arek Sarkissian asked his opinion of the die-in, second-year MBA student Chris Lutter replied he thought the event was "ridiculous." "How would they feel," he asked, "if their family was killed in an attack by a terrorist?"

|

|

|

Mr. Lutter's question and the implication behind it ¸ that opponents of the war in Iraq or the "war on terror" would change their tune if they had personally felt the impact of terrorism ¸ have been repeated a lot in recent months. As such, it's a notion worth examining. Does personally feeling the effects of a terrorist attack predispose a person toward vengeance? Does campaigning for peace somehow deny the suffering of those whose lives were impacted by the events of Sept. 11?

At face value, remarks like Mr. Lutter's seem to make a lot of sense. The al-Qaeda attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon was an act of destruction and wanton violence unknown on U.S. shores since Pearl Harbor. It filled Americans of all stripes ¸ from Drew Carey to Toby Keith ¸ with an overwhelming desire for retribution. Surely those who personally experienced Sept. 11, or who lost friends and loved ones to the attacks, must feel this lust for revenge more strongly than anyone, right? You might think so. But you might be surprised by the reality.

Just a few weeks ago, a group calling itself "September Eleventh Families for Peaceful Tomorrows," issued a statement saying it "condemns unconditionally the illegal, immoral, and unjustified U.S.-led military action in Iraq." Formed by representatives of at least 50 families who lost loved ones on Sept. 11, Peaceful Tomorrows has consistently campaigned for a peaceful, reasoned response to the fear and anger generated by the terrorist attacks. The group's position on Iraq is clear: "as family members of Sept. 11 victims, we know how it feels to experience ╬shock and awe,' and we do not want other innocent families to suffer the trauma and grief that we have endured."

The members of Peaceful Tomorrows have learned what many other victims of violent crimes have discovered: while suffering horror or terror often creates a desire to inflict violence in kind, such vengeance rarely brings real closure. Indeed, it often does quite the opposite, stirring up new hate, begetting new violence. Take the violence in Israel and Palestine, for instance ¸ each new suicide attack or Israeli incursion inspires Israelis and Palestinians to bigger, more destructive acts of "retribution" in a pathological desire to hit harder than they've been hit, inflict more pain than they've suffered. The result is an endless cycleof increasingly desperate and intractable violence.

To be sure, not all victims of terror share this view. Many doubtlessly welcomed the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. But as our nation pursues its imagined revenge against the people of Iraq, as many Americans hail the "war on terror" as a way to soothe new-found fears or restore a national ego bruised by the vulnerability the terrorist attacks displayed, it is worth remembering that many of those who personally bear the weight of Sept. 11th's horror, like the thousands of New Yorkers who filled the city's streets in anti-war protests last month, do not share their enthusiasm. Instead, they echo the words spoken by Andrea LeBlanc ¸ whose husband Robert died on Sept. 11 ¸ at a peace rally in New Hampshire last month:

"I know that it is easier to fear and hate someone if you see them as ╬other' Ě or if you don't see them at all. I know that it is easier to be for a war if you don't think about the people whose lives will be destroyed. I know that violence begets violence."