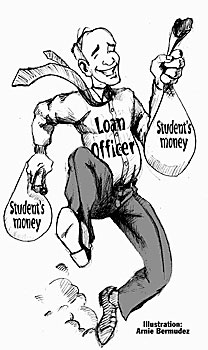

Illustration by Arnie Bermudez

|

|

By Ryan Johnson

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Thursday, September 30, 2004

Print this

A guaranteed 9.5 percent return. It's a bankers' dream.

Higher than lending to home-buyers. Higher than lending to companies. Heck, that's higher than lending to most developing countries.

But due to a 10-year-old loophole recently brought to light by the Government Accountability Office, it's the return that certain companies are getting by loaning to students. Students only pay 3.4 percent, but the government makes up the difference.

Who needs to lend to Uruguay when Uncle Sam will guarantee you more?

Banks such as Nelnet, the biggest abuser of the loophole, have been asking themselves the same question. In the last few years, banks have been stepping up the practice to the point where it's costing the government $1 billion per year.

And it's all coming out of the coffers of the student loan program. These 9.5 percent loans, which make up less than one-tenth of the number of loans, nonetheless make up three-quarters of the expenditures of the program.

Why the high rate? When the program started, it used Reagan-era interest rates, and the rates weren't indexed to adjust to market conditions. Nobody anticipated the loophole staying around as long as it has, to an era with rock-bottom interest rates.

Back then, it helped make banks willing to lend to students. But now it's a drain on the system, paying levels far higher than it would take to make banks willing to do so.

A primer on interest rates: In the banking world, the riskier the loan, the higher the interest rate the bank receives.

Broke students are certainly one of the more risky demographics to loan to. After all, if a student runs up $100,000 in debt only to decide that, well, they don't have the stomach to be a doctor and want to go into construction, then the bank has a major problem.

But the second the U.S. government guarantees those loans, they go from risk concerns to the single most secure source of payment on the face of the earth.

A two-year government bond is currently yielding about 2.5 percent. A 30-year bond, less than 5 percent.

These 9.5 percent loans are equally unrisky, so why do they yield several percentage points higher?

They shouldn't. What these payments amount to is a handout. When the banks can secure loans, even loans from the government, at low levels and then receive 9.5 percent, it's like printing money.

The Education Department maintains it can do little to stop the problem. Meanwhile, when Nelnet sent them a letter stating their intention to dramatically increase their portfolio of the loans, the department took more than a year to issue an ambiguous, empty letter.

Nelnet then sent out a press release about its intention to increase the number of loans, skyrocketing its shares up a third of their value. That increase is money that should go to providing more loans and grants to students instead.

How many times do we have to hear about the government letting swift, fast acting private industry milk it like a cow?

Now the House has passed a resolution, but how long will it take the Senate to pass theirs?

So what's the solution? The obvious one is to close the loophole, which the GAO says the president can easily do. Call it a loophole, call it manipulation, call it corruption: this subsidy needs to stop, and only special interest group explanations can explain why it is still there.

Longer term, however, we need to think about what role private institutions should play in administering student loans. Simply put, if the government is going to assume the risk, why not just have the government administer the loan? Or have the banks administer it, with the funds coming from the government, and with the bank receiving a commission for finding the students.

But when a loan is as safe as a U.S. government bond, it shouldn't yield more. Especially when it comes out of a program that students need to afford college.

This issue isn't getting much national attention. An article in The New York Times about it showed up in the business section, not the news section.

But it is important enough for students to make it an issue.

But until then, time to start a bank.

If anyone has approximately $150 million to start a bank or an insurance company, please contact Ryan Johnson, an economics and international studies junior, at letters@wildcat.arizona.edu.