|

|

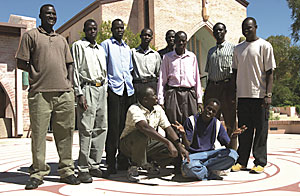

Photo by Will Seberger/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

A group of the Lost Boys gathered outside Grace St. Paul's church Sept. 26 for a portrait.

|

|

|

Andrea Kelly

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Monday, October 4, 2004

Print this

How a group of child refugees from the Sudan made their way to the UA

In 2002, a group of the Lost Boys of Sudan living in Tucson spoke at the UA. They said they had dreams of someday wearing the university "A." Fourteen of them now do, and they have each walked thousands of miles to get here.

The Journey

Their journey began about 17 years ago, when the Lost Boys of Sudan fled from a war that has killed at least 2 million, by conservative estimates. They all left the largest country in Africa between 1987 and 1989 because they were scared.

They were also targets.

The young boys (the youngest in Tucson was five when he left his family) were expected by cultural and tribal standards to defend their people.

The Sudanese government, by killing young boys, tried to protect itself against the threat of an army of strong young men years later.

With the knowledge they gain in the United States they will help others in their tribe, the Dinka, who have suffered through the civil war in Sudan for 21 years.

But they will have to wait to do so.

The Lost Boys are refugees. They fled Sudan for protection from the war, and some say they think they will be killed if they return before the religious and political war ends.

The war is between the Sudanese government, the National Islamic Front and rebels in the south, the Sudanese People's Liberation Movement.

The NIF has tried for years to convert or kill Animists and Christians in the southern part of Sudan. In response, the Southern People's Liberation Army formed in an effort to defend the religious freedom of southern Sudan.

The boys who ran are called the Lost Boys of Sudan, but they say they are not lost. They are displaced from their homes and families in Sudan, but they know where they are and who they are.

|

|

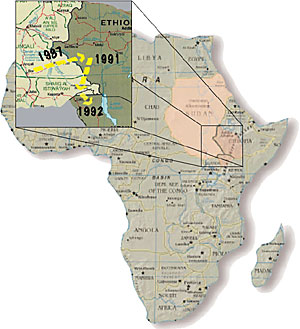

MAP COURTESY OF THE CIA

|

The route walked by the Lost Boys between 1987 and 1992.

|

|

|

They are not boys either. They left their country as boys and quickly grew into men.

Now they are trying to absorb as much education as possible in America, and working hard to accomplish that goal.

Peter Ayuen, 25, a political science junior, estimates he spends 20 hours a week on homework, then works at least 20 hours each weekend at Desert Life nursing home.

John Majok, 23, a public management and policy and health and human services senior, is taking 18 credits and works full-time at Fidelity National Title.

When they are not studying or in class, they work. They work to pay their bills, to send money back to family in Africa and to save enough to someday return.

They dream of a peaceful Sudan, a country they can call home - not just where they are from, but where they live.

They are Sudanese, but they haven't been to the Sudan since 1992.

For some of these men, attacks on neighboring cities prompted the journey.

For others, family forced them to leave so they wouldn't be hurt if an attack did occur. But all of them left their homes, ran for days, walked for months and found themselves in Ethiopia.

"The day of the attacks I was out in the field with goats and sheep. It was about 4 p.m. local time. I was pulled along by someone running. I didn't want to go, but I was pulled," said Khoor Lukuach Malual, 26, an electrical engineering and mathematics junior.

They spent four years in Ethiopia that were filled with school, missionaries and struggles. Many of the Lost Boys were baptized there.

Others were already baptized Christians before they fled, and a few, like Khoor, waited to be baptized.

In 1991 another war erupted around them.

As civil war broke out in Ethiopia, the boys were once again on the move - back to Sudan, back to the war they had escaped and back to the struggles along the way.

Just like the trip into Ethiopia, the trip out of the country was filled with tragedy, sorrow and sights so gruesome some of the men won't talk about what they saw.

The Dinka are the largest tribe in the Sudan, and though many of their traditions vary from clan to clan, cultural consistencies remain.

Daniel Keech, 24, a business finance sophomore, said a Dinka boy is not allowed to see a dead person until he is 18.

|

Everyone has a tragic experience, and everyone has their own stories.

– John Majok

|

|

But as they walked, the Lost Boys buried best friends, brothers and cousins by the thousands.

Lions and hyenas attacked the large groups at night, starvation and dehydration during the day.

Between 1987 and 1989, 125,000 boys escaped the country as refugees. By August 1992, only 16,000 remained alive, Khoor said.

"Everyone has a tragic experience, and everyone has their own stories," John said.

The animals were the biggest threat at night.

"During the night we lost a lot of people coming from Ethiopia to Sudan." Daniel said.

Practically anything walking, anything crawling, posed a threat, said Abraham Deng Ater, 25, physiology and pharmacy junior.

"You didn't know how you were going to survive," Abraham said.

To avoid starvation, they searched for leaves and berries. When those ran out, they tried trees.

The situation did not improve once they reached the refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya, in 1992.

There, they were given corn, two handfuls of beans and sometimes wheat flour every two weeks, Daniel said.

Abraham estimated they received a total of two pounds of food every two weeks.

They had to make it last, so even though the United Nations was providing food, the boys still went days without eating.

"There was not enough food," Abraham said.

|

I wanted to die; I felt useless.

- Khoor Malual

|

|

Dinkas are known to be the tallest culture in the world. Dinka basketball player Manute Bol, who played in the NBA in the '80s and '90s, was 7-foot-7, and Abraham said the Lost Boys knew taller men in Africa.

The physical challenge of survival took a toll on the boys.

"We grew very skinny, (but) still grew tall, from nature," Abraham said.

He is 6-foot-3 and said if he and the other boys hadn't been refugees, they would have been bigger and taller.

The men in Tucson range from 5-foot-4 to 6-foot-6. Abraham said among Dinka, he is of average height.

Besides underdevelopment, they had to struggle against their own wills.

"I wanted to die. I felt useless," Khoor said.

He said he felt like there was nothing he could do to help himself or others, and that he tried to die during the long treks.

"I waited to die but I couldn't," Khoor said.

Once, when they tried to stop for a rest, the boys were attacked by people from a nearby village.

In that attack, 12 boys were killed, which Khoor said was a low number.

"That was a good thing - very few died of 16,000," Khoor said.

After walking from Sudan to Ethiopia and back, the boys walked along the southern border of Sudan until they got to Kakuma, Kenya.

They stayed in Kenya from 1992 to 2001, where they went to school, played basketball and lived together in the clay homes they built themselves.

Religion

Khoor said he was confused about the conditions they faced, as boys kept dying and British missionaries tried to introduce religion into the boys' lives.

"Sometimes I think, 'If there is a God, why did he let this happen?' To punish a child who has not done anything is not good," Khoor said.

When the boys reached Ethiopia, missionaries took care of them. Most of the Lost Boys were baptized there and chose their Christian names.

John said he wanted to follow in the footsteps of the disciple John, so he adopted his name.

"He's the only one that wrote the theme of the Bible," John said, "that God so loved the world, God loved all mankind."

Khoor said he waited longer to accept God. He wanted to make sure he could believe in such a thing before being baptized.

Khoor left Sudan in 1987 when he was nine, and became Christian in 1992.

Most of the other Lost Boys converted in 1988 and 1989.

"I became Christian last because I was looking for the God," Khoor said.

Khoor was in Pochalla, Sudan, on the journey between Ethiopia and Kenya when that search ended.

He was fishing in a river when a lion walked by. When the lion didn't attack him, Khoor, whose name means "lion," said he thought it was God who had protected him.

Missionaries arrived in Sudan in 1905, and by 1991 most of the Dinka tribe was baptized, Abraham said.

It took a while because the Dinkas didn't trust the missionaries at first.

"When the missionaries came to Sudan, they acted like traitors - they would take a child and never come back," Abraham said.

"That's what missionaries did. Some were Christian and they really want people to know the word of God, (but) some were not."

When Abraham met the missionaries in Ethiopia he said he was ready to convert.

"Oh yeah, I was happy - that's what I was looking for," he said.

Many of the Lost Boys in Tucson go to an Evangelical church, Grace St. Paul's, near campus every Sunday.

|

|

photo Courtesy of Peter Arok

|

The Lost Boys commemorate the beginning of the civil war in Sudan every May 16. The event includes ceremonial dancing and costuming, as seen in this May 2004 photo.

|

|

|

America

After nine years in the refugee camps the men knew they might soon be relocated, so they prepared to move. They watched for announcements daily to see if their names appeared on lists of American cities.

The Lost Boys' moves were sponsored by non-profit human service agencies in the United States and Australia.

The ones sent to Tucson received help from Jewish Family and Children's Services and the International Rescue Committee.

These agencies sponsored the boys in pairs, so they would be sure to have at least one other Lost Boy to live with.

In April 2001, the first of the Lost Boys left Africa. More than 70 Lost Boys took the 36-hour flight to Tucson. Some didn't eat the entire time because the food on the planes was foreign to them.

"The salad was like grass. I eat salad now, but not then," Abraham said.

When they arrived in the United States and went through Immigration and Naturalization Services, officials had to guess the boys' ages. Many were assigned a Jan. 1 birthday because they did not know their actual birthday or age.

After a conversation with his father a few years ago, Daniel said he thinks he is closer to 29, even though he is 24 according to legal documents.

Daniel is one of the lucky ones who has contact with his immediate family. The only people the men can call are family members who have moved to Uganda or Kenya. The men who have family there usually talk to them about once a week. Very few of them know where their parents are, except that they are somewhere in Sudan.

U.S. agencies found housing for the Lost Boys and paid their first four months of rent. They helped the men find jobs and get into schools.

The Lost Boys filled out I-94 forms, declaring their status as political refugees.

Once here, they applied for green cards, which can take up to a year to get. Some who applied later are still waiting for permanent cards.

After they have their green cards, it can take up to five years for them to be eligible to apply for U.S. citizenship.

They speculate it will take longer, though. They moved to the United States between April and August 2001, before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Since the attacks,the INS has been absorbed by the Department of Homeland Security, which could mean a longer wait for U.S. citizenship for the 3,800 Lost Boys in America. It also means the 1,000 still in Kenya do not know when they will be able to start life in a new country.

|

|

Photo by Will Seberger/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Daniel Keech, a pre-business sophomore, washes a bowl at his house near North Park Avenue and East Prince Road. Five Lost Boys live in the house.

|

|

|

A new world

In the United States, the Lost Boys were thrust into a world they'd never imagined, a culture they didn't understand and a community like none they'd ever seen.

"Coming here happened like a dream. I didn't want to come here. I didn't know what it's like," Khoor said.

The Lost Boys left their families at such a young age, they never learned how to cook. Abraham said the Lost Boys boil all their food because it's the only way they know how to cook.

For a weekend lunch, they chose a Chinese buffet. Bior Keech, 19, Daniel Keech's stepbrother, said it is easier to choose what to eat when they can see it first. Menus can be difficult sometimes, and they said they still haven't adjusted completely to the taste of American food.

They drink juice and soda. They cook rice, pasta and chicken, a change from the food they had in Kenya, although most still only eat one meal a day.

Because Bior lives in a guesthouse, attached to a house in which five other Lost Boys live, he doesn't use his kitchen. Instead of food, the counters and cupboards are full of basketball shoes.

Bior went to Amphitheater High School for two years, where he played basketball and ran cross country and track. He plays soccer with other Lost Boys on the weekends.

Bior said he liked high school better than college, because it felt more like a family.

The men came from a community culture in which everyone worked together and families were huge by American standards. Most of their fathers had multiple wives, because the larger the family, the more people there were to raise cattle, goats and crops and operate a family business.

The day he left, Khoor said he had been in a field with goats, sheep and calves. Now he lives in a dorm with a TV, laptop and air conditioning.

Many of them have driver licenses and their own cars, while others prefer bicycles.

Technology is new to the refugees, too.

When Peter Ayuen got his cell phone, he said he couldn't put it down.

"The first time I had a cell phone, I wanted to use it all the time," he said.

He didn't know he had to charge it, and was confused and thought it was broken when it stopped working.

|

|

Photo by Will Seberger/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Peter Nyok sits in his J.P. Industries office Sept. 7. Nyok helps out with the firm's payroll and other office tasks several times a week.

|

|

|

Bior showed him how to charge it so he could continue to use it.

"It would be really tough without (a) cell phone and computer," Peter Ayuen said.

Abraham said he adjusted to the technological lifestyle because there was no other option.

He compared the American lifestyle to the herding lifestyle of the Dinkas.

"It's like cattle. Back in Sudan, everyone has cows. Here you don't have cows," he said. "It would be difficult to not have (technology). We can't live without it. You'd get bored."

The Lost Boys also have a unique outlook on others' social hardships.

After fighting to stay alive for years, they recognize when others are struggling.

"I like to help homeless people, because I know how hard it is," Khoor said.

"Many of them didn't choose that life; those should not be blamed."

Khoor said he collected 700 aluminum cans for a homeless man he used to see regularly at the Pima Community College downtown campus.

"All of the Lost Boys, we like to give them anything we have," Khoor said.

The Lost Boys also remain concerned for the people struggling through life on another continent.

They check Web sites like sudan.net or splmtoday.com daily for news on Sudan.

After a Wildcat football game a few weeks ago, they turned to CNN Headline News.

As headlines and stories cycled across the screen, a short story on the genocide in Darfur, Sudan, came on.

The room of men, who were all talking at once, immediately fell silent.

Everyone listened as the news update reported 50,000 had been killed and at least

1 million had been forced from their homes since the intense fighting began there.

As they listened, Bior's only reply was, "Damn."

When it was over, Peter Arok, a civil engineering junior, asked, "Where will they all go?"

|

|

Photo by Will Seberger/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

David Nyok, a biochemistry and molecular biophysics junior, catches up on his homework Sept. 7.

|

|

|

Education

"The Lost Boys' goal is to get education and go back to Sudan," Bior said.

John started school at Pima Community College in August 2001, just two months after he got to the United States. He graduated with honors as the valedictorian of the class of 2003.

Most of the other Lost Boys started school in 2002. Nine of the 14 UA students graduated from Pima last May.

These men are working toward the future of the country they had to leave.

|

|

Photo by Will Seberger/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

David Nyok, a biochemistry and molecular biophysics junior, goes for a walk on campus near the old chemistry building on Aug. 7.

|

|

|

Most say they will someday go back, and plan to use what they learned to better the situation there. "The most important reason for my education is to give back," John said.

Abraham is studying physiology and pharmacy because doctors are not easily accessible for the Sudanese.

He said Bor, the largest city in the southern part of Sudan, used to host the worst fighting in the country. "Now there is no fighting but there is hunger and disease. There are no clinics set up. People have to go to the Congo, Uganda, Borador (for medical help).

"People are dying because there are no medical centers. They burned down medical centers (in the war)," Abraham said.

The country is without basic medical supplies, he said. "That's why I need to go to med school. People are dying of disease that they should not be dying of - malaria, tuberculosis, worms, appendix ruptures."

The Boys are using the education they gain in the United States to help their country, and are forging a relationship between the two nations.

|

I bother myself to go to school because I want something out of it. I know I have this opportunity so I want to use it.

– Peter Ayuen

|

|

"I am a man of two countries," Khoor said. "We are here for education and to let our politics be known. It looks like the world doesn't know about it. We are here as ambassadors, to build relationship with America and Sudanese."

They want change, and they want to be the ones to make the changes in their country.

"We can do something wonderful. Sudan should not be Third World," Khoor said.

John wants to study international law and someday be a diplomat on foreign affairs issues in Sudan. Over the summer, he interned for Rep. Jim Kolbe, R-Ariz., in Washington, D.C. and spoke on the House floor.

"I can apply my skills anywhere. My aim is to give back to the community the skills I have acquired," John said. He was the first Lost Boy to graduate from Pima and the first Lost Boy in the nation to graduate with honors.

"We are all smart but our commitment and intellect make us succeed," Khoor said.

Peter Ayuen said his journey is not over.

"People should know I did not succeed yet; success comes as opportunity. Other friends didn't get opportunity to come here," he said. "I bother myself to go to school because I want something out of it. I know I have this opportunity so I want to use it."