|

|

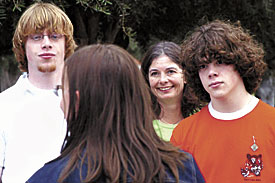

Randy Metcalf/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Spanish and communications senior Meighan Burke gives a campus tour to the Mergel family yesterday afternoon. Paul, 16 (left), and Jack, 15, came to UA with their mother Beth from Michigan to see what UA has to offer for their college education.

|

|

By Jeff Sklar

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Wednesday February 26, 2002

When the University of Michigan entered the national spotlight last year for its policy on the role of race in admissions, UA President Pete Likins said he would stay out of the debate.

Now, shortly after filing a legal brief opposing an alternative to Michigan's policy, he says he can't avoid the discussion.

Likins plans to push forward with admissions proposals that will give special consideration to minorities as part of his plan to make the UA more diverse, even as the Supreme Court considers the Michigan case, which could have major implications on the role of race in university admissions.

Diversity has been a centerpiece of Likins' Focused Excellence plan, and even if the court outlaws the use of race as a factor in university admissions, Likins said he is confident the UA will mold a diverse student body.

"You need to be in an environment with people who don't look like you," he said. "Managing a diversity of populations is important for us."

The court will decide later this year whether the University of Michigan will be allowed to give admissions advantages to certain ethnic minorities, and could, in the process, overturn Regents of Univ. of California v. Bakke, the landmark 1978 case that allows universities to factor an applicant's race into admissions decisions.

Likins wants to see Bakke upheld, and last week he filed a legal brief arguing that universities cannot become diverse simply by granting admission to a certain percentage of students at the top of their high school class.

Several states, including California and Texas, use the system Likins argued against. The Bush administration also considers it a fairer alternative to the Michigan system, which uses a point system to give preferential treatment to minorities.

Likins rejects the administration's argument, saying it rarely works.

"Obviously that doesn't work unless the high schools are segregated," he said.

Likins prefers a more individualized system, which gives applicants credit for overcoming adversity. Saying that minorities inherently must overcome obstacles, Likins thinks they should benefit from such a policy.

"It's hard to argue there's no handicap to being black in America," Likins said.

Under an individualized system like the one Likins prefers, administrators would look at factors besides a student's performance in school to see if they faced challenges that prevented them from getting in the top 25 percent of their class.

Students who overcame challenges would be admitted while other students from more privileged backgrounds with similar grades and test scores would not necessarily be admitted.

Students whose parents never attended college, or students who worked many hours in high school to help pay the bills would benefit from a system like this, Likins said.

This more individualized outlook toward admissions could also help admissions officials identify students who might not appear likely to succeed in college, said Randy Richardson, vice president for undergraduate education.

"Race and ethnicity by themselves are not predictors of success but many times students from low socioeconomic environments do better than standard measures would

predict because they haven't had access to the same kind of resources," Richardson said.

That logic sits well with Socorro Carrizosa, director of Chicano/Hispanic Student Affairs. She agrees that many people have preconceived ideas that Latinos are less intelligent than white people, and that even a Mexican accent can put people at a societal disadvantage.

"We hear a French accent and we think that's so beautiful · we hear a Mexican accent and all of a sudden we think that person isn't educated," Carrizosa said.

Minority students face similar challenges to white students from disadvantaged backgrounds, said Alex Wright, director of African-American Student Affairs.

Wright has seen that phenomenon firsthand, when he worked in a town with a large minority population, but also with groups of poor white people. He prefers not to look at university admissions as an issue of race, but an issue of whether people come from advantaged backgrounds.

"It's not a black and white issue," Wright said. "There's a lot more to this than affirmative action."

Likins wants to consider applicants' backgrounds, but he doesn't want people to think that a certain set of circumstances in their lives should guarantee them admission. Just because students have worked hard doesn't mean they should have access to any university they want, he said. That's been the issue in the Michigan case, where

individual applicants are suing the university for denying them admission in favor of minorities who they felt were less qualified.

To Likins, it's a question of university management. Rather than looking at admissions decisions from the perspective that individual students are entitled to an education, he wants to consider what's best for the university as a whole.

A population of all white males couldn't meet that goal, he said.

"Boy, that's not a good learning environment," Likins said.

Carrizosa takes a practical approach toward the importance of a diverse student body, saying it better prepares people to work in a world where they will be surrounded by different races.

"It provides for stronger leaders for the business community," she said.

As the UA's admissions process becomes more selective and individualized, Wright said he hopes an essay becomes part of the application all students must fill out. When students' essays are considered, it allows the university to create a student population that's not just diverse in skin color, but in thought.

"You only have one aspect of diversity when you're talking about color," Wright said. "I hope that what the university is talking about is diversity across the board."

Keren G. Raz contributed to this report.