|

|

DEREKH FROUDE/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Robert Green, the president of The Integrated Biomolecule Corporation, holds out a vial which is valued at about $24,000 for its 100 milligram contents. Green moved into the Science and Technology park almost 10 years ago and is preparing his company to move on to a building in Oro Valley.

|

|

By Jeff Sklar

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Friday May 2, 2003

Editor's note: This is the second in a two-part series on UA research in biosciences.

On a recent trip to Washington, D.C., Dr. Ray Woosley had a conversation with a person he described as a prominent national scientist.

When the discussion turned to biosciences research, the scientist asked Woosley, UA's vice

president for health sciences, about the state's decision to step up its research in the life sciences.

The reason: the scientist wanted in.

"He asked, ╬What's going on in Arizona?'" Woosley said. "Is there room out there for us?"

That response is typical of what UA and state officials hope to hear as biosciences research becomes a high priority in Arizona. And though UA is spending nearly $120 million to construct two buildings that would house biosciences researchers, they expect a return on their investment that will stretch far beyond the university's walls.

Playing catch-up

Few people at UA will say the university conducts research to make money. But it doesn't take much to get administrators talking about the return they're looking to get on their biotechnology investment.

Ask anyone in the medical field how to judge a university's research prestige, and they'll say it's through competitive grants from the National Institutes of Health. According to the NIH Web site, of the nearly $17 billion awarded in grants during 2001, UA brought in about $90 million, a number university officials say is far too low.

But collaboration in the biosciences could send that number skyrocketing, said Dr. Fernando Martinez, a co-director of the Institute for Biomedical Science and Biotechnology, which will be housed in a $65.7 million building near the Arizona Health Sciences Center.

|

|

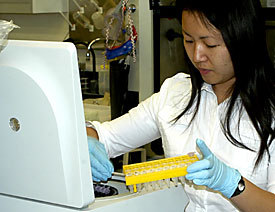

DEREKH FROUDE/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Anne McElhaney, chemist for the Integrated Biomedical Corporation, works with some nutrient samples last Thursday at the Science and Technology Park south of Tucson.

|

|

The NIH specifically looks for researchers who collaborate, and that has cost UA in the fight for NIH resources.

"Many times we have not had here the critical mass of researchers that would allow us to be competitive for these type of grants," Martinez said. "We could do much better if we created an environment in which we have the ancillary services and core facilities that would foster collaboration between people in different areas."

But when it comes to that structure, Arizona is lagging nationally. Areas like Maryland, San Diego and Portland, Ore., have leapt ahead of Arizona when it comes to conducting top research. That's one of the reasons the philanthropic Flinn Foundation commissioned a study last year that outlines how Arizona would catch up to those areas.

In late 2002, the Batelle Memorial Institute, a non-profit research organization, came back with an answer. Start slowly, the report said, in areas like neurobiology, cancer research and bioengineering, where the state is already strong. Then branch out to broader areas.

"The first thing we need to do is just expand our research in these areas," said Dick Powell, UA's vice-president for research and graduate studies.

Those broader areas include plant genomics, and other areas with wide-ranging human health implications.

The Batelle report is clear: It will take years, perhaps a decade, for Arizona to catch up with top research locations. But UA officials said they're willing to wait, and that the key to succeeding is attracting enough researchers.

Once those researchers are here, and the collaborative mechanisms are in place, Martinez says, UA's competitiveness with the NIH could skyrocket.

If UA can land those grants, it would bode well for the university not only in terms of its academic prestige, but its ability to create jobs and inject money into the local economy.

Last month, two UA researchers released a study that found that the $285 million the university now attracts in grant money generates a $385 million impact on the local and state economies.

Those grants create university jobs, and those employees spend their money locally. The university also spends money purchasing equipment and supplies from local businesses, and contributes more than $20 million in tax revenues to local and state governments.

"It's actually a nice contribution from the University of Arizona," said Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi, one of the study's authors.

Though improved grant competitiveness is likely the most profitable way UA could benefit from biosciences research, Powell also points out another way. University researchers sometimes develop their own products that they can market to private companies.

When they do, the university gets licensing fees.

Last year, this activity, which is known as technology transfer, brought UA $800,000, a number Powell says isn't nearly as big as it should be. But with an investment in biotechnology, he expects that figure could rise. Perhaps, he says, the university could even hit a research "home run," like the University of Florida did when it created Gatorade.

Entrepreneurial science

About 25 minutes southeast of UA's main campus lies the university's Science and Technology Park. Amid pristinely manicured grass and covered walkways, about 30 high-tech companies that employ 6,200 people lease space from the university in hopes that the park's facilities can help them jump-start their businesses.

Only a few of those employees are directly involved in biotechnology, but the ones who are say that their relationship with the university has been instrumental to their success.

Robert Green's company was the park's first tenant. In 1994, around the time UA purchased the 1,345-acre facility from IBM, Green opened Integrated Biomolecule Corporation at the park.

Nine years later, he's getting ready to move out. His company is moving to Oro Valley late this year, but Green remains certain that it will keep close ties with the university long after it moves away from UA's facilities.

"If it wasn't for (the park's directors) and this park, there probably would be no Integrated Biomolecule," Green said.

Integrated Biomolecule works with pharmaceutical companies to research and develop new drugs. At his company, they don't dream up ideas for new drugs; they develop the drugs.

In his office, Green keeps a tiny vial filled with a powder-like drug his company developed. It's worth $24,000.

Green's company employs 10 people, and he says he does almost all of his hiring straight out of UA. That's good news for the graduates he hires, because jobs in the biotech industry pay well.

According to Dr. Raffi Gruener, the science and technology park's scientist-in-residence, someone with a bachelor's degree in the biosciences can earn $50,000 straight out of school. A newly minted doctorate could make $90,000 or more.

"These companies create really high-quality jobs that pay good wages," said Bruce Wright, a UA associate vice president and director of the science and technology park.

Aside from the owner/tenant relationship, the companies say they see other benefits from partnering with the universities.

Green said that when his company was still young, its relationship with the university was "essential." Without facilities, he needed the university's labs and equipment.

"They always found a way for us to do it, and we always paid our fair share," Green said.

A close relationship with companies like Green's also serves the university well. As industries move to the state and form university partnerships, UA can make more money in areas like technology transfer, Powell said.

"They feed off each other," he said.

University faculty, too, will likely benefit from a higher commitment to research in their fields, Gruener said.

"The more companies come to the area, the more it stimulates faculty," Gruener said.

That would make it easier for faculty to market their discoveries, which would mean financial gain for both the researchers and the universities.

|

|

CHRYSTAL MCCONNELL/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

Yu Cai, a plant science graduate student, extracts DNA using a centrifuge machine in her plant genomics lab. Administrators have said they want to expand plant genomics research.

|

|

For UA, that likelihood is increased even more by the fact that lawmakers want to give the university the ability to own stock in companies started by their researchers. Faculty start those companies when their own research becomes marketable.

Powell downplayed the financial significance of that possibility, which could make its way onto the ballot in an upcoming state election, but said it would still be a slight boon for UA.

"This will be nice to have this option," he said. "It'll make deal-making easier."

But it could also create conflicts of interest for faculty, warns Paul Sypherd, a molecular biologist who was UA's provost for much of the 1990s. It could make faculty fearful of doing research because of possible financial consequences, he said.

"I think it's a dangerous and swampy area for the university to get into unless the process is thought through and safeguards are put in place," Sypherd said.

Sometimes, Powell said, companies give universities large sums of money to do specific research, a situation that could compromise researchers' academic integrity.

But this has never happened at UA.

"I think to say that is a potential problem that the academic community in this country is cert true," he said. "But I don't' see anything on the horizon at the University of Arizona where this is going to cause us any problem."

Wooing the businesses

In Tucson, there aren't many biotechnology companies yet, but officials hope that once word of mouth spreads of the state's investment in the field, companies will come.

The good news for UA ¸ high-tech industries cluster around universities. That's happened in places like San Diego and Maryland, but President Pete Likins believes there's room in the biotechnology industry for Arizona.

"People are saying, ╬Things are happening in Arizona. Maybe that's where I should establish my company,'" Likins said.

The key to bringing new companies to Tucson, and to Arizona, is creating industry clusters.

These clusters form when businesses doing similar work open in the same area. It's a phenomenon throughout industry, Likins said, pointing to the cluster of microelectronic industries around the University of California - Berkeley, near the Silicon Valley.

The most prominent industry cluster in Tucson studies optics, and administrators credit its success to its proximity to UA.

The biotechnology cluster is much smaller, Wright said, but it's only two years old and growing. And it's likely to start growing faster, especially if UA keeps investing in biosciences.

"They need access to the research enterprise of a university," Wright said.

That access is important because university research tends to be more theoretical, but it forms the basis for the practical, technological applications that can make companies money.

"Companies need new products, they need new info about how cells behave and how cells screw up," Gruener said. "Their interaction with people who do bench research on a day-to-day basis is very important to them."

It also means good news for the local economy, which Gruener says needs to harness the advantages of high-tech industry.

"To be based almost entirely on tourism simply doesn't work anymore," he says.

Part of Gruener's job is to travel the country persuading biotechnology companies to relocate to Arizona. When he travels to Washington, D.C., to a biotech conference this summer, he'll be showcasing the collaborative opportunities at UA, and the chances those companies will have to work with other groups across the state.

Woosley, the health sciences vice president, said he's seen evidence that companies around the nation are interested in Arizona. Aside from the scientist he talked with while in Washington, D.C., he said he's also heard from drug companies interested in moving to the area.

"It's word of mouth," Woosley said. "It's amplifying like a snowball."