|

|

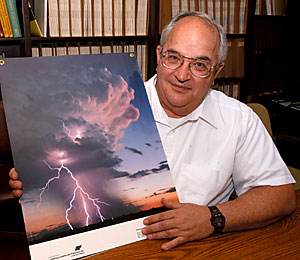

WILL SEBERGER/Arizona Daily Wildcat

|

E. Philip Krider, an atmospheric sciences professor, displays an example of the multiple-strike lightning he studies yesterday afternoon. Krider is researching methods of predicting rainfall based on lightning patterns.

|

|

|

By Joe Ferguson

Arizona Daily Wildcat

Thursday, August 26, 2004

Print this

For the past year, E. Philip Krider has been watching the skies.

The University of Arizona atmospheric sciences professor believes studying lightning strikes will lead to a reliable system to predict rainfall. Krider believes this system will one day rival radar mapping in predicting storms.

Krider and his team of graduate students have been studying thunderstorms in the Walnut Gulch Experimental Watershed near Tombstone. They have been working with the U.S. Geological Service and a company specializing in lightning detection. The results from the yearlong study have brought surprising results.

"We have a regular, reproducible relationship between cloud to ground (lightning) strikes and the amount of rainfall," said Krider.

According to Krider, for every cloud-to-ground strike measured, there are approximately 20,000 cubic meters of rain.

"That would fill about two Olympic swimming pools," said Krider.

Krider said his team has studied both large and small thunderstorms, and the results are similar regardless of the size of the thunderstorms.

In addition to predicting the amount of rainfall, Krider believes his data can predict the peak of rainfall. Rainfall will be the heaviest several minutes after the peak amount of lightning.

"By plotting the rate of when the lightning peaks, rainfall will be the heaviest five to 10 minutes later," said Krider.

In massive storms, Krider said, there is a longer delay between the lightning peaks and the rainfall peaks. Krider said these storms have higher updrafts, and it takes longer for the rain to fall.

"Usually it is about 20 minutes," he said.

The idea came to Krider about two years ago while he was working at the Kennedy Space Center. Krider noticed a correlation between the frequency of the lightning strikes and the amount of rainfall when reviewing data after a storm.

Krider and his team are working closely with Vaisala, which runs the U.S. National Lightning Detection Network. It uses more than 100 ground-based lightning sensors to detect cloud-to-ground lightning across the continental United States. There are sensors in Tucson, Yuma and Lordsburg, N.M. Each sensor can accurately detect lightning strikes up to 600 miles away.

This is not the first time Krider has worked with Vaisala. In the late 1970s, Krider helped develop the lightning sensor for Vaisala, although the company was called Lightning Location and Protection at that time. Although he is no longer affiliated with Vaisala, the UA has a contract to share data with the company.

Krider defends his research results by pointing to data collected during massive storms in the upper Midwest in 1993. While he said the method used to measure rainfall then was different than his own, he believes the data validates his research. During this massive storm, Krider said the rainfall was measured at 200,000 cubic meters of rainfall per recorded lightning strike.

Krider said he is finalizing a paper to submit his findings to a scientific journal in the next few months.